For more than a decade now interest rates on deposit accounts have been less than 1%, and currently they are well under 1%. At present, the highest interest rate I am able to find on a “high yield” savings account is 0.6%. Are you feeling taken advantage of yet? Me too! Are you concerned that if you keep too much money in cash you’re guaranteed to lose purchasing power to inflation? I sympathize completely. Do you find yourself annoyed that the only way to generate a return on your hard-earned savings, and possibly defeat the inflation monster, is to put it at high risk? I get it. We’re all in the same boat. Fret not.

I’m going to write a short series of articles that discuss how to generate safe returns in a world where it seems the central banks want to push us into risky assets. I think you’ll agree with me that with a little creativity some decent inflation-busting returns can be generated without risking taking a bath in the next bear market in stocks or real estate crisis (without a doubt the next crisis is coming, we just can’t predict when or how severe). In this article, I’m going to discuss the true interest rate on cash for those who are willing to be a little creative. By the way, this will apply to any form of liquid savings (e.g. precious metals), so what you’re about to read is not limited to cash. I’d appreciate your comments in the comments section to gauge whether more articles such as this one are of value to you, my readers.

The return on cash is higher than its interest rate, much higher actually

Let’s face it. Cash is boring. It just sits there. Lately, it seems it has just sat there losing value each and every year to inflation because its interest rate is lower than the rate at which the cost of living escalates. To add insult to injury governments tax the nominal interest earned as if it’s all profit (completely disregarding the fact that part of the interest rate is coverage of cost of living inflation). So why even hold cash?

Whether we like it or not, all of the goods and services we buy on a regular basis are priced in units of cash. Need to buy groceries for the family this week? That’ll be $200 (or whatever your local currency is). Want to put gasoline in your car this week? That’ll be $30. Interested in keeping your internet service next month? That’ll cost $75. Want to keep the bank from foreclosing on your house? That’ll cost $1000 per month. The list goes on and on. Life costs money, and being able to come up with that money when the bills come due is important. It is for this reason most people keep a certain amount of money in the bank. Unfortunately, most people keep very little money in the bank. The median family bank balance, according to the Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, was $5,300 in 2019.

This low number helps to explain why there are so many consumer options available to smooth out cash flow. Can’t afford to pay cash for a replacement car? The car company is more than happy to arrange financing (sometimes even offering zero interest rate financing if you don’t mind paying a higher price for the car than you otherwise might be able to negotiate without the zero interest rate loan). Don’t have the cash to replace the refrigerator when it breaks down? You can use your 15%-24% variable APR credit card and hope to be able to pay the balance down quickly (I don’t recommend this). Can’t pay your auto insurance premium for the year in one lump sum? The insurance company is more than happy to let you pay monthly in return for a “convenience fee”. I can go on, and on, and on. But I won’t. I think you understand where I’m going with this. The main benefit of having ample cash is it can remove the presence of financial vampires in our lives. Let’s quantify the effect of a couple of these financial vampires to estimate the true benefit of having some cash on hand so that we can tolerate some lumpy and large expenses.

Example #1 – Self-insuring auto collision

Last year we had a substantial wind storm at our house. It resulted in a gardening cart being blown into the driver-side front quarter panel of my car, leaving a fist-sized dent. I immediately called my insurance company to ask them for advice. Since the same insurance company underwrites my homeowner and auto insurance it was only a single phone call. Their advice? Send pictures so that the claims adjuster could estimate the cost of the repair and send me a check to have the bodywork completed. The insurance company estimate, $960, was remarkably close to the estimate my chosen body shop gave me. I was thankful I had decided to carry coverage for “other than collision loss” on our cars. The only cost to me was the $250 deductible. I filed the claim, received a $710 check from the insurance company ($960 – the $250 deductible), and got the bodywork completed with only a minor out-of-pocket cost. It was relatively painless, or so I thought!

Several weeks ago my auto policy renewal documents arrived. I noticed the total premium was substantially higher than it was last year and so I called my insurance agent. It was not easy solving the riddle of what factors specifically contributed to the premium increase, but after running a few case studies we learned that my insurance company changed my risk tier, resulting in a premium increase of $197 per year as a result of me filing the claim. My goodness! Obviously, I’m shopping around for a new insurance company as I write this, but I’m told by my insurance agent that seeing an increase in premium after a claim is not uncommon. The insurance adjuster I spoke to last year told me the claim should not impact our rates. He was wrong. It looks like the insurance company is going to recover their cost, the $710 check, in 3.6 years. Funny, when I asked my insurance agent how long this claim would impact my premium he said 4 years. Had I known all of this last year I would have just paid the full $960 out of pocket and not even bothered with the claim!

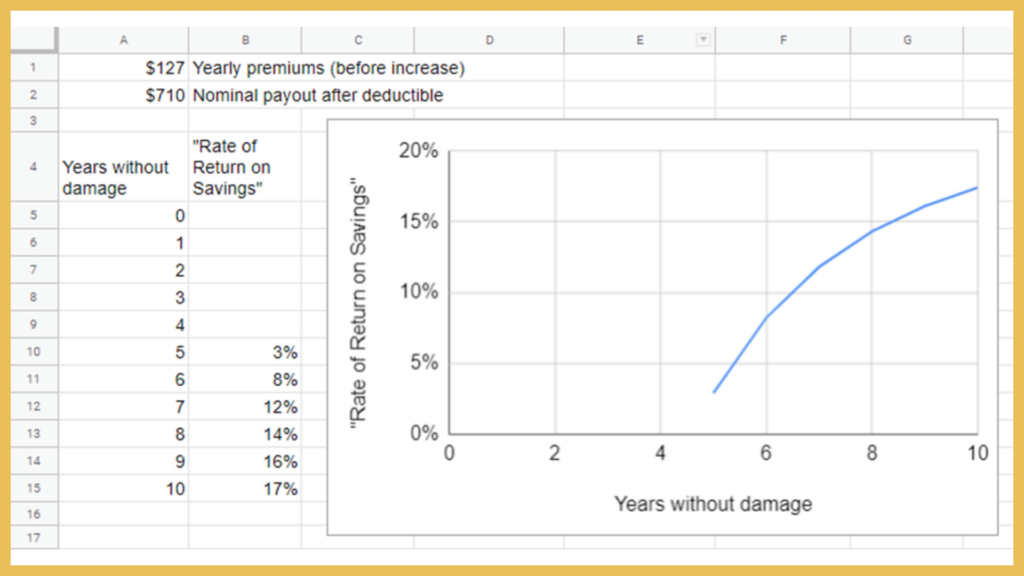

This made me wonder. If a person were to self-insure for things like this and save the premium what would the “rate of return” on that saved cash be? In the case I described above the incremental cash needed to self-insure is $710 (this is the nominal value of the check the insurance company wrote). The yearly premium saved would be $127 per year (the cost of my “other than collision loss coverage). The “rate of return” will depend on the number of years that pass without a claim. In this example, the rate of return is calculated and shown in Figure 1.

Obviously, self-insuring is a bad idea if a claim will be filed within a few years of paying for the insurance, but if sufficient years pass then the total premiums saved will exceed the cost of the potential check and we can talk about a rate of return on this fallow cash that is not being put to work in the stock or real estate markets. If 5 years pass without damage the rate of return is 3%/yr. If 6 years pass without damage the rate of return is 8%. As more time passes the rate of return increases and plateaus near 20%/yr. The less frequently we expect to make a claim the more profitable it will be to stockpile cash and pay for repairs ourselves.

Figure 1: Scenario for “rate of return” on cash used to self-insure auto collision

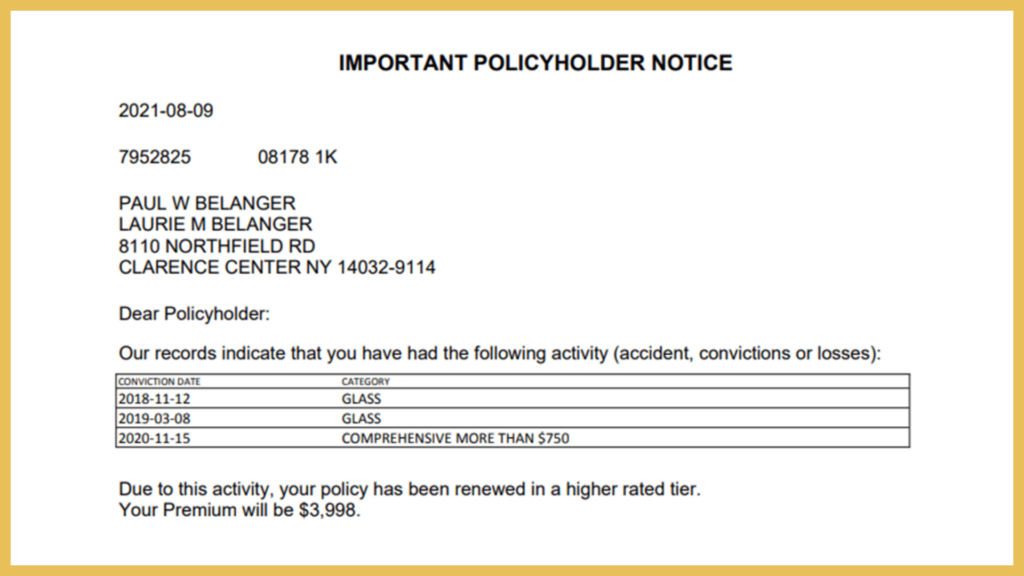

But is this really the whole picture? Let me direct you to an exhibit included in my policy renewal packet.

Figure 2: The claw back

As Figure 2 shows, the claim of more than $750 bumped us into a higher risk tier. This is what triggered the increase in premium of $197/yr. Let’s include the impact of increased premiums for the 4 years immediately following a claim and see how it changes the math.

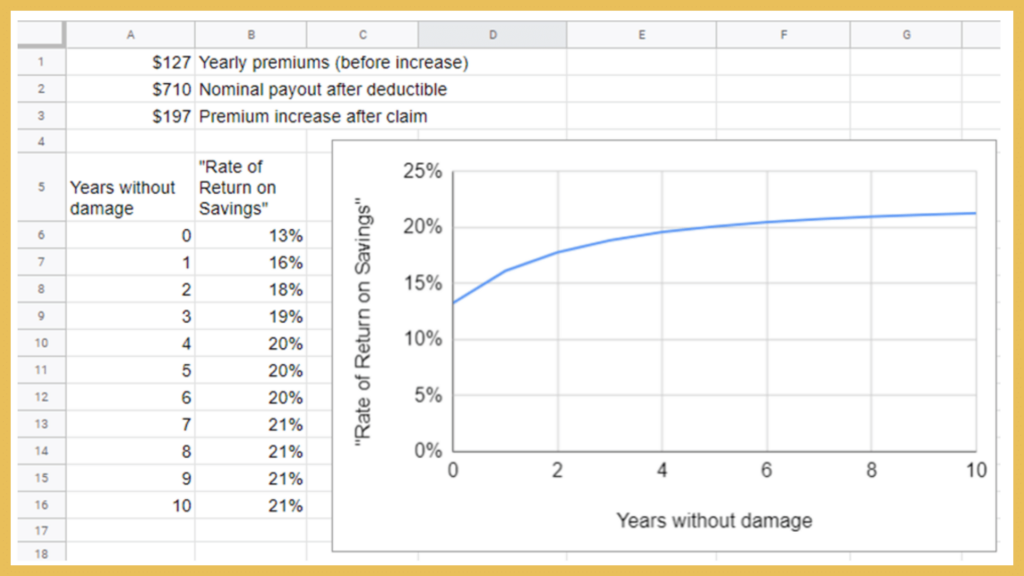

Figure 3: Including the impact of increased premiums after a claim

Figure 3 shows quite a different story. When the impact of higher insurance rates after a claim is considered it makes sense to self-insure for damage (at least the level of damage of this claim) no matter how long we expect it will be before we need to call on the insurance company to perform under its contractual obligations. Let’s suppose we decide to forego the insurance and just save the $710 the insurance company would be paying us in the event of an accident and stick it in a savings account. Obviously this is a $710 negative cash flow but we’d also be saving the $127 initial year premium. Our cash flow in this first year is -$583. But we’re saving the 4 years of increased premiums in the following 4 years ($197 each). The rate of return on this cash flow stream is 13%/yr. If we expect not to have an accident for several years the rate of return grows to 21%/yr. Not bad for having some cash around doing nothing (hopefully)!

How can this type of “return” be so easily overlooked? The reason is that we are trained to look at the return on an investment in terms of the income it generates, not in terms of the expenses it can help us to avoid. This is faulty logic. An investment is anything that can favorably impact our cash flow situation in a manner that adequately compensates for the cost of the investment. It doesn’t matter if the improved cash flow is an increase in income or a decrease in outgo. Speaking of which, there is an additional benefit associated with avoidance of expenses we didn’t even include here. Taxes. Expenses avoided are always AFTER-tax, whereas the income is generally when it is earned. What kind of a rate of return would be needed to generate an after tax return of 13%-21% per year? That depends on your tax rate. If your total tax rate on income is 20% you would need to find an investment that generates a return of 18%-26% per year.

Example #2 – Choosing high deductible health insurance

Here’s another big insurance example. It may not apply the same way in every country, but in the US it’s a big one and can be an instructive example to illustrate the power of having cash to handle expenses. Health insurance. I am a big proponent of having health insurance. According to a study in 2007 62.1% of bankruptcies in the US were related to medical expenses where 92% of the bankruptcies had medical debts over $5000.[1] Having adequate medical insurance is a critical part of financial planning. But what is adequate? Is there such a thing as purchasing too much insurance? There is if you have some cash.

Because medical expenses for unexpected care can run into the hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars, very few people can afford to self-insure completely. Most of us will need to buy medical insurance. But given that insurance company headquarters are the largest buildings in town (maybe with the exception of bank headquarters), it would seem to be to our advantage to buy as little insurance as possible and cover what we can with cash savings. How can we do this? Simple. Buy a high deductible health plan.

https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343%2809%2900404-5/pdf

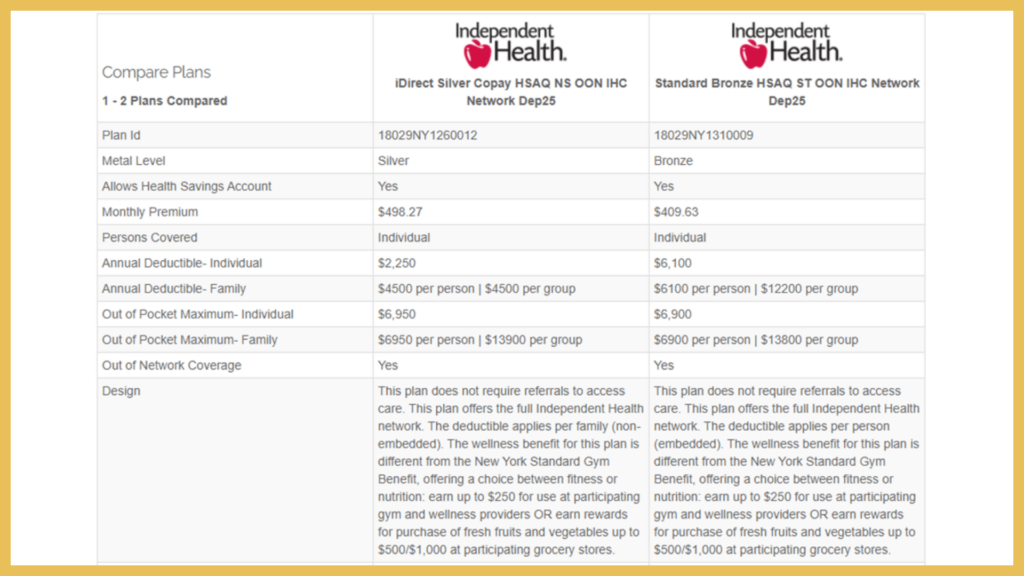

Figure 4: Comparison of health insurance premiums and deductibles

Many people, at least in the US, enroll for healthcare through their employers. Usually there is an option to pay a higher premium for a low deductible plan or to pay less for a high deductible plan. Each employer will offer different options. Unfortunately I cannot disclose the details of the plans that were offered to me; however, now that we have healthcare offered on exchanges I can use some publicly available information to highlight the benefits of a high deductible plan. Figure 4 shows a side by side comparison of two very similar plans offered to individuals.

Notice that the silver plan costs $5979 per year (unsubsidized) and has a deductible of $2250. The bronze plan costs $4915 per year and has a $6100 deductible. The out of pocket maximums are nearly the same for each plan at about $6900. The bronze plan will pay 50% of costs between the $6100 deductible and the $6900 out of pocket maximum. The silver plan has a complex schedule of fixed copays for different types of services between the $2250 deductible and the roughly $6900 out of pocket maximum.

The way insurance plans work is you pay 100% of all costs up to the deductible, then you pay a cost share above the deductible up to the out of pocket maximum. Above the out of pocket maximum the insurance company pays 100%. For the bronze plan the difference between the deductible and out of pocket maximum is very small and so what the buyer of the bronze plan is really buying is limited financial exposure to a year of catastrophic medical costs. He or she is essentially self-insuring up to $6900 whereas the buyer of the silver plan is self-insuring up to $2250 with some limited exposure to costs incurred above that level.

Let’s assume a person has a choice. He or she could decide to keep $6900 in the bank (or HSA account – more on that in a moment) to cover a year of potentially catastrophic health care costs and buy a bronze healthcare plan or alternatively keep $2250 in the bank and buy the more expensive silver healthcare plan. The difference in cash that needs to be set aside is $4650. The potential savings in premiums each year is $1064. If annual healthcare related expenses remain under $2250 (the deductible for the silver plan) then the rate of return on this “cash investment” is 22.9%. It’s actually even better than that. If the cash is placed in a Health Savings Account (HSA) the at least part of the contribution becomes a tax deduction. In that case the rate of return will be higher than 22.9%.

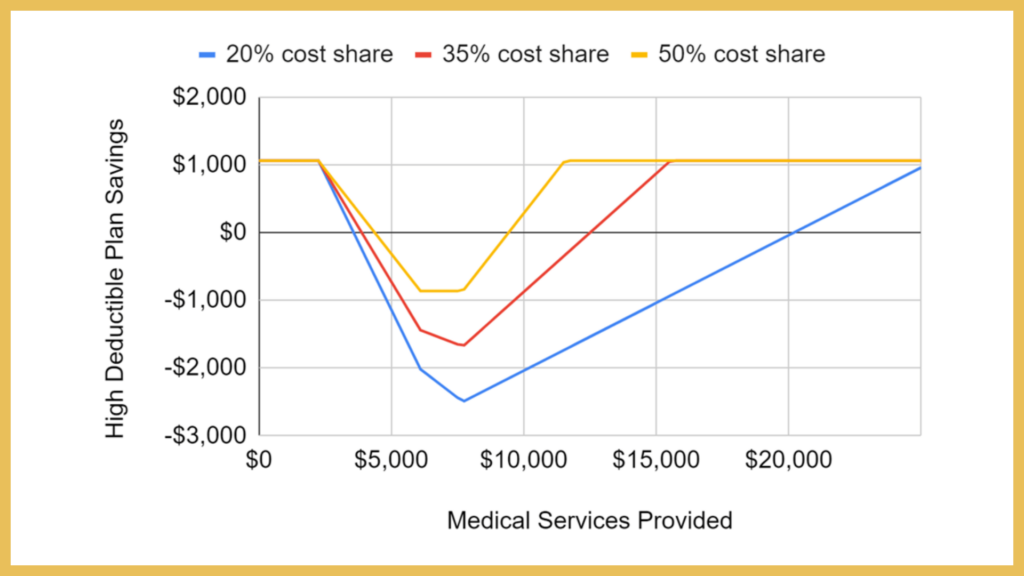

What if medical costs in a given year are higher than $2250? Everyone’s situation is different after all. Once actual costs exceed $2250 the “rate of return” on the choice to stockpile cash and choose the bronze plan starts to decline.

I put together Figure 5 to show what happens to the yearly savings of picking the high deductible plan under various scenarios. On the horizontal access is the amount of medical services provided. The silver plan pays out nothing until services exceed $2250, so anything below that level is a constant yearly savings for the bronze plan of the $1064 premium difference. Once medical services exceed the deductible, the silver plan starts paying out. It was unclear from the schedule of benefits what the percentage cost share was but it’s likely to be somewhere between 20%-50% on average, so I modeled 3 levels of cost share. As the level of medical services increases the benefit of using the bronze plan decreases. There is no savings for the bronze plan when medical services exceed about $4000. But a funny thing happens. As medical services continue to increase eventually a point is reached where the bronze plan again becomes the prudent choice! Why is this? Because the bronze plan caps out of pocket costs at a level of $6900. Regardless of cost share assumed for the silver plan eventually a point is reached where the silver plan holder also hits this upper limit. Beyond that point the silver plan and the bronze plan provide the same benefit! The bronze plan is financially a better choice for modest expenses or catastrophic level expenses. It is only when expenses are moderate that buying more insurance turns out to be the best choice.

Figure 5: Yearly savings for various levels of medical system use

In this article I have shown how it can be of great advantage to hold enough cash to reduce insurance coverage, pay a lower premium, and thus self-insure. The reason why this works should be obvious. Insurance companies are in the business of making money for their shareholders. The less insurance you buy the less profit they make from YOU. Of course this requires doing something that few people, especially today, want to do. That is to store up cash. Doing so can save several thousand dollars per year, enough to generate a “return on cash” of 13%, 20%, or more. Your situation may be completely different. You’ll have to run your own numbers.

I hope that this article inspires you to analyze cash in a different way and to think about some creative ways to put it to use to improve your cash flow position. I’d appreciate your comments, even if you did not like the content. I’d like to be sure to write content that is useful for you and your feedback will help me to do so.

You can buy Paul’s book by clicking here: Evidence-Based Wealth – How to Engineer Your Early Retirement if you are seeking to master your financial destiny so that your life will belong to you and not to your employer?

This book will provide you with enough basic knowledge that you can develop and execute your own program for achieving financial freedom at an early age. It will also expose you to some fairly advanced tricks and new ways of interpreting financial information, protecting and building wealth, and planning for short and long-term financial goals.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and entertainment purposes only. All opinions and information are for demonstrational purposes and do not constitute investment advice. This information is being presented without understanding your specific circumstances or financial situation. If you need advice, please contact a qualified financial adviser, tax accountant, or an attorney, in your country before making any financial decisions.